The pandemic has been a particularly strange time for digital nomads. On a positive note, nomads have observed their seemingly farfetched wish for the mainstreaming of remote work become a reality almost overnight.

At the same time, travel bans, reduced airline schedules, and quarantines have drastically curtailed global mobility. As we head into year two of Covid-19, even experienced digital nomads might benefit from a moment’s reflection on how to best capture the benefits of their lifestyles in a changed environment.

Our research on digital nomads and their community in Bali, Indonesia, suggests ideas that may be used to improve the lives of remote workers of all stripes. For instance, we learned that control over one’s day-to-day working environment is crucial to the wellbeing of many nomads.

Remote “rookies” who have suddenly been thrust, with their laptops, into a corner of their bedroom at home for an eight-hour day during lockdown may not feel much agency about their environment. But the pandemic is temporary – even if it doesn’t seem so right now – and remote work privileges seem likely to endure in some form.

Eventually, workers will have both the ability and desire to move beyond the loneliness of the bedroom workspace. What will they seek?

Over and over during four years of research on digital nomads, we heard two seemingly opposing themes:

1) DIGITAL NOMADS SEEK FREEDOM

2) DIGITAL NOMADS WILL TRAVEL EXTRAORDINARY DISTANCES TO FIND COMMUNITY

What we discovered is that digital nomads have created a new form of community, one that prizes both individual freedom and strong, face-to-face connections.

Freedom – Still a Core Value

Without a doubt, freedom is digital nomads’ most important value. As they describe it, freedom means defining oneself as an individual in explicit contrast to social structures and institutions, especially those that appear to offer security and stability in return for conformity to rules or other collective social obligations to families, communities, organizations, and societies.

Paul, a 39-year-old English marketer, expanded on this:

The driver is that you’re doing it for yourself… What gives me inspiration, zest for life is this idea of freedom. Being able to do whatever I want to do, whenever I want to do it, from wherever I want to do it, is so empowering for me. It’s palpable. I can taste it. It’s a wonderful feeling, and it far exceeds my expectations of what I thought it would ever be like in those daydreams that I must have had many times.

Paul Tweet

The scaling of remote work means that many, many more people will experience aspects of the freedom Paul describes. This is an exciting development, and one that digital nomads often expressed to us as a wish for their fellow professionals back home.

As remote work becomes an expected part of life as a knowledge worker rather than a privilege requiring tough negotiations with a manager or even leaving full-time employment behind, its rebellious image may fade somewhat. In many ways, this will be a good thing.

For instance, parents will not have to take up arms against the system to gain flexibility in childcare. However, these changes may also weaken aspects of remote workers’ cherished identities. If you had to give up your job to work remotely, how will you feel if your successors do not have to give up anything at all to have the same privileges?

Community – Face to face is a must too

I actually travel to places where I feel very good and where I think there are good people because when you travel it can be quite lonely sometimes and having the right people around you— who maybe also stay long- term— it’s just very nice to have. I feel like in Bali I have this. –

Belinda, 22-year-old German digital nomad working as a virtual assistant and entrepreneur Tweet

Digital nomads would seem to be the very prototype of individuals to embrace virtual communities as primary. However, those we met clearly and firmly rejected any claims that technology substitutes for face-to-face community. Although digital nomads do use and value online sources of community, they tend to view such communities as inherently limited.

Rebecca, a Canadian business consultant and entrepreneur, explained that virtual communities are often more transactional:

“I’m involved with a lot of Facebook communities and entrepreneurial circles, but no one’s really invested in your success. It’s just like ‘What resource can you give me?’… You have to have your guard up a lot.”

In contrast, digital nomad hubs such as Bali or Chiang Mai bring together a critical mass of people who share common values and pursuits. They don’t share an employer and they may not share a profession, but their similar values around work bring them together nonetheless.

Check out this clip and see the digital nomad lifestyle in Chiang Mai

What does a community of individuals who value freedom above all else look like? Our research revealed its two defining characteristics to be fluidity and intimacy. Reflecting the desire for freedom, digital nomads have normalized inflows and outflows in their communities.

Grace, a 30-year-old public relations consultant from the U.S., observed that there is a kind of support in understanding that everyone comes and goes, often at a moment’s notice: “Your friends in this community, they know what it is to say, ‘I’m not sure when I’m going back home.’ And they also understand if you have to all of a sudden go back home. There’s no shame. There’s no guilt.”

Such fluidity would seem to work against the formation of deep relationships. Yet their desire to build strong ties to one another in an environment where people come and go leads digital nomads to prioritize the rapid escalation of in-person relationships, building intimacy in the community.

In digital nomad hubs such as Bali, a steady stream of networking events, peer-to-peer learning forums, and social outings provides formalized opportunities to engage in a ritual we call telling your story. Almost everyone we met was eager to tell their story, usually in the form of a personal journey toward a new work identity. Most nomads we met were also eager to hear others’ stories.

Nomads’ freedom enables this, and allows them to consider nearly anyone else they meet in the lifestyle as a potential friend. And as Laurence, a 26-year-old fashion designer from the U.S., told us, “No matter how busy you are, there’s always time for lunch with a friend.”

Coming out of the pandemic, remote workers will need community if they are to sustain fulfilling work lives without relying on conventional office arrangements. Contrary to the beliefs of many managers, our research does not suggest that it is essential even for full-time employees to meet their needs for community with others from their organization.

And although it is nice to have some contacts with others in the same profession, working community also does not have to be defined by professional similarity. Instead, our research identifies similarity in values as an alternative foundation for work communities.

By helping remote workers find and connect with others whose work values are aligned, managers might improve satisfaction and performance in their teams while gaining access to fresh ideas to fuel creativity through employees’ expanded networks.

Digital nomads’ insights on the future of working community

Digital nomads have been alternately romanticized and vilified of late in mainstream media, yet few seem to have taken seriously the implications of their triumphs and struggles for the development of communities to support remote workers.

Our research on digital nomads and the communities they create suggests that individuals who surround themselves with others they perceive to be like-minded about key work and life values may experience greater well-being.

Considering the large proportion of people who do not wish to return full-time to the office, it seems clear that many do not find such like-mindedness in the organizations that employ them. This creates problems but also opportunities, and we note in the U.S. alone the many initiatives by cities, states, and private investors to lure remote workers, all of which might bring more like-minded individuals into closer proximity. Internationally, initiatives to allow digital nomads to work in many countries are also expanding. Obviously, not all of these new options for community will be equally popular.

However, we are optimistic that the breadth of experimentation in new platforms for place-based communities aiming to attract remote workers will help to both fuel and accommodate the growth of long-term remote work beyond the pandemic.

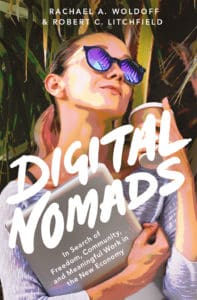

Get the book on Amazon now!

About the book authors

Rachael A. Woldoff, PhD

Professor of Sociology Department of Sociology & Anth.

Rachael A. Woldoff is an urban sociologist and Professor of Sociology.

Her research and publications have focused on neighborhood crime and disorder, urban redevelopment, and racial/ethnic differences in neighborhood attainment, as well as the subjects of neighborhood racial change, gentrification, housing affordability, and creative class cities. Her work has appeared in Social Forces, Urban Affairs Review, and Urban Studies.

Rob Litchfield

Associate

Professor at

Washington &

Jefferson

College

Robert C. Litchfieldgm is an associate professor in the Department of Economics and Business at Washington & Jefferson College, where he teaches organizational behavior, human resources management, and strategic management. He received his Ph.D. in industrial/organizational psychology from The Ohio State University. Rob’s research focuses on creativity and innovation, identity, and the future of work and has been published in academic journals

Newsletter

SUBSCRIBE NOW

Join thousands of other Digital Nomads already in our community!

[…] do not have to invest time into planning which can be quite a time-consuming process for digital nomads. They can simply join a program and pay a flat-rate fee which will cover most […]